The Conception Bay Museum Association Inc. was founded in 1970 for the purpose of preserving local history and assisting in the tourism potential in Conception Bay, one of the most beautiful and historic areas of the province. Opening a regional museum in Harbour Grace’s old Customs House and developing a ‘Historic Trail,’ from Brigus to Placentia, were the first steps of the committee’s five-year tourism plan for the region. In addition to the Conception Bay Museum, other sites on the Avalon peninsula provided the basic framework for the proposed ‘Historic Trail,’ such as Castle Hill National Historic Park in Placentia, the Heart’s Content Cable Office, the Fisherman’s Museum at Hibb’s Cove, Gull Gallery in Clarke’s Beach, and numerous other federal and provincial historic sites. Other plans included restoring the fortifications at Carbonear Island and establishing a sealing museum at Brigus.

In spring 1973, the Committee on National Museum Policy granted National Exhibition Status to the proposed museum inside the old Customs House and provided financial assistance to prepare the building for various travelling exhibits. The building, owned by the provincial government, was given over to the control of the Conception Bay Museum Association to obtain funding and exhibition status. The provincial government completely rewired the building for the restoration, and the National Museum Policy Board in Ottawa offered $31,960 in 1973-74 for restoration and renovation; display and display equipment; lighting and display lighting; humidification and dehumidification systems; a new heating system; curator’s salary; and office supplies. With this funding, the committee set out to find a fulltime curator to oversee the renovations, set up the displays and promote the organization’s mandate. The committee soon found its ideal curatorial team: Jerome Lee—the son of Martin (“Mac”) Lee, vice-president and one of the driving forces behind plans for the Conception Bay Museum—and his wife Pamela Barton.

Jerome Lee and Pamela Barton-Lee, ca. 1974.

Originally born in Placentia, Newfoundland, and Mississauga, Ontario, respectively, Jerome and Pamela first met at Glendon College, York University, and soon fell in love. In Toronto Pamela lived with eight other people in a cooperative setup, working to support herself at the Steak-n-Burger and volunteering with disabled children at Bloorview School. Jerome worked in a house established to help Atlantic Canadians having trouble in the big city. Together they travelled extensively in Europe, where they attended the University of Marseille, France. Upon returning to Toronto, Jerome enrolled for a year at Ryerson, studying photography, and Pamela took courses in Journalism.

The couple were offered the chance to move to Jerome’s home province in 1973, and on April 14, the two were married in a small ceremony in their living room. After celebrating they packed their Dodge camper van and headed for Newfoundland.

The couple and the committee’s volunteers soon got to work renovating the old Customs House and its neighbouring grounds. Pamela was largely responsible for the exterior plans of the museum and landscaping. These plans included fixing the two 1854 gas lamps to the entrance of the museum and installing the early iron water tanks in the park for the 1974 season. In the next phase of development, Pamela and the committee planned to construct a stone wall around the grounds, continue landscaping, erect several historic markers, and develop a walkway to nearby Colston’s Cove, where John Guy landed salt in 1612.

Jerome was engaged in overseeing the details of the interior renovations and organizing displays for the planned May 1974 opening. The completed museum was to feature refinished birch and the restoration of its grand mahogany staircase. Jerome’s friend Ron Smith, an interior decorator visiting from Toronto, helped paint the interior its blue and ivory colour scheme.

In the February 7, 1974, issue of The Compass, Conception Bay’s regional newspaper, Jerome outlined the plans for the museum: “The ground floor of the building is funded by the federal government’s National Museums as a National Exhibition Centre. The two rooms of that floor are being converted into galleries with complete environmental control: temperature, humidity and lighting. The walls are panels covered with Irish linen. They will provide a neutral backdrop for exhibits which will come from all over Canada. The travelling exhibits will cover a large range of subjects, including Science and Technology, History and the Arts. The National Exhibition Centre will give people in this area a chance to see some samples of the other cultures of the other nine provinces.

“The two rooms on the second floor will be reserved for local exhibits. Private collectors in the Conception Bay area will use the museum facilities to display their collections to the public. Local residents and tourists will have the chance to see any valuable articles from the past. At opening the exhibit on the second floor will be ‘Sealing in Conception Bay.’

“We are also hoping that the second-floor space will be used by local artists for contemporary arts and crafts displays. History can, perhaps, be brought to life if it is seen in relation to present day activity and contemporary art can also gain from the historical perspective.”

The young couple wanted the community to have a personal involvement with the museum, to feel they had an important role in its success. At the heart of their vision for the museum was to engage youth and the community through both education and culture. They hoped to conduct classes in both photography and crafting during the winter months, outside of the seasonal tourism industry.

Pamela Barton-Lee wrote a regular column for The Compass newspaper during her time in Conception Bay.

During the renovations, the two lived in Carbonear, where Pamela began work as a receptionist at The Compass. There she wrote her “MScellany” column, which focused on local, national and international women’s issues. The column was a warming dialogue with women in the area, urging them to shed some of their traditional, restraining customs.

In April 1974, Jerome and Pamela headed to Toronto on a mixed business and pleasure trip. Jerome’s friend Ron went with them. In Halifax, the three stayed with Jerome’s sister Dianne on the drive through. After eating breakfast with Dianne and saying their goodbyes, the three continued their journey on a foggy day in Nova Scotia.

Tragically, at around 11 a.m., their van collided with a parked truck—whose axle had broken the previous night—outside of Amherst, Nova Scotia, killing the three passengers. Pamela was in a coma for nine hours at Amherst Hospital before passing away. Jerome was 26, Pamela 24.

Funeral services for Pamela, Jerome and Ron were held on Tuesday, April 9, in Harbour Grace. The ecumenical service, representing the faiths of the decreased—Anglican, United and Roman Catholic—was held at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, just down the road from their planned museum. The young couple were laid in a common grave at the Roman Catholic Cemetery in Harbour Grace. They would have been married a year only five days later.

Despite this tragedy and monumental setback, the committee pressed on with their plans for the museum opening, doing their best to implement Jerome and Pamela’s vision for the building. Instrumental in this work were Jerome’s parents, Mac and Marie Lee, who stepped in and completed the project exactly as their son and daughter-in-law had planned.

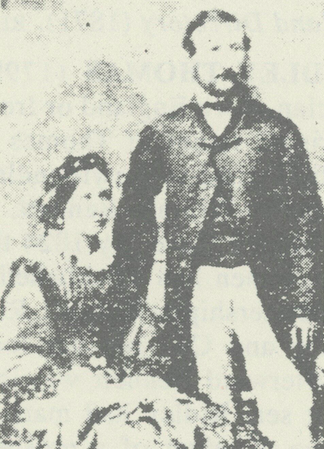

A headline in The Compass advertising the museum’s opening, 1974.

On Friday, May 17, 200 delegates from the Canadian Museum Association’s 29th conference, held in St. John’s, came to Harbour Grace for the opening of the Customs House as a National Exhibition Centre. The four busloads of people were treated to a seafood luncheon and reception at the Harbour Grace Legion prior to the dedication ceremonies. At the reception, Mayor Ted Pike welcome the delegation and Bill Parsons, vice-president of the Conception Bay Museum Association, spoke on behalf of committee president Gordon Simmons. Parsons remarked on how pleased they were to host a national delegation and complete their first milestone: to have the old Customs House designated as Harbour Grace’s first museum. Parsons singled out Mac Lee and Gordon Simmons for their initiative and desire to see the building open for spring 1974. He also expressed his condolences to Mac and his wife Marie on the loss of their son Jerome and daughter-in-law Pamela.

Robert Broadland reveals the National Exhibition Centre plaque, May 17, 1974.

At the old Customs House, Robert Broadland, member of the Consultative Committee on National Museum Policy, revealed the designation plaque on the building’s exterior. “I hope to God that the wind doesn’t take this away,” he said, laughing. Inside, Newfoundland artist George Noseworthy’s fifteen “rhythmics” were displayed on the first floor, with Stephen Racine’s Indigenous photography exhibit from Canada’s west coast, on loan from Ottawa’s National Museum of Man, on the second. In a letter of thanks to the Conception Bay Museum Association, Barbara Riley, an attendee from Ottawa, noted how “difficult it was to get everyone back on the buses…some delegates would have stayed taking pictures of Harbour Grace until the sun went down.” The new National Exhibition Centre hosted over 4,000 people during its opening season in 1974.

Though the National Exhibition Centre successfully opened in the old Customs House, the committee’s plans for local history exhibits were delayed until the 1975 season. In January 1975, the Local Initiatives Program (LIP), a federal funding initiative, granted $16,096 for six workers to upgrade the old Customs House, in preparation for a summer 1975 opening; and the National Museum Policy Board in Ottawa again offered the Association a sizable grant of $26,000 for 1974-75.

G.A. Frecker opens the Conception Bay Museum to visitors, June 14, 1975.

On Saturday, June 14, 1975, after five years of diligent work, the Conception Bay Museum opened its doors to the general public. Finally, the local history of Conception Bay would have a permanent showcase in Harbour Grace. New Association chairman Judge Rupert Bartlett and Mayor Ted Pike welcomed the gathered crowd. On hand for the opening was Dr. George Alain Frecker, then Chancellor of Memorial University and former Minister of Provincial Affairs in Premier Joseph Smallwood’s government. In his political role, Frecker offered early moral and active support to Gordon Simmons and Mac Lee, believing the region’s past was indeed worth celebrating. Although it was a happy occasion, Frecker spoke of Jerome and Pamela’s leading role, drawing a strong emotional reaction from those who knew the young couple.

Harold Horwood reveals his plaque, detailing the history of Peter Easton, June 14, 1975.

Well known writer and Confederation architect Harold Horwood was also in attendance. Horwood unveiled a plaque—his composition—detailing the legacy of “arch-pirate” Peter Easton in Harbour Grace. On the grounds, hoisted by students from St. Francis High School, a replica of Easton’s black pirate flag flew, alongside the flags of Conception Bay’s famous mercantile houses—the Munns, Ridleys, Jobs, Rorkes, and Bowrings. Jerome’s grandmother, Bride O’Keefe, sewed the flags for the occasion.

Inside, exhibits on local history were finally displayed to the public. On the second floor, the seal fishery exhibit envisioned by Jerome was proudly displayed, with items on loan from the Newfoundland Fur and Hide Co. For photography enthusiasts, the third floor displayed old archival pictures of Harbour Grace, taken long before the devastating 1944 fire, which forever altered the prominent downtown area of the community. During the 1975 summer season the local boy scout and girl guides clubs graciously volunteered their time to work as onsite interpreters.

Today, the Museum strives to implement the vision of its early founders, particularly Pamela and Jerome’s community-centred approach. As such, the Conception Bay Museum showcases the wider Baccalieu Trail region but recognizes the importance of Harbour Grace as its home base, where its biggest supporters lie. The aim for this building is not simply a museum but a cultural hub for the community, a place for locals to feel proud.

In recent years, with the help of committed volunteers, talented coordinators, and engaged student employees, the Museum has expanded its horizons. New programming has included book launches and signings; popular Halloween Haunted Hike fundraisers and heritage walks; a regularly updated website, database, and electronic archive; concerts at the church hall; scavenger hunts for children; and pub quiz nights. Television features on CBC’s Still Standing, UNIS TV’s Hors Circuits II, and in Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism marketing are recent highlights of the institution’s continued growth and regional importance. And in fall 2018, after partnering with the municipality and the provincial government, the Museum Board restored the Colston’s Cove Stairs, one of Pamela and Jerome’s first plans for the outside grounds.

Much has changed in the long 150-year history of this building and its 50 years as a museum. However, the building’s various historical uses showcase its longevity and importance in Harbour Grace. If volunteer enthusiasm is any indication—the Board of Directors currently welcomes 20 members—the Conception Bay Museum should be around for another 50 years yet.

Selected Founder Profiles

Martin (“Mac”) Lee

Born in Harbour Grace, Mac Lee left his hometown for the United States at the age of 15. He returned to Newfoundland in the early 1940s, working at the Argentia naval base in the department of public works, where he remained until returning to Harbour Grace in 1974.

Always very involved in public affairs, he was a founding member of the Placentia Area Public Library and the Placentia Area Historical Society. In addition, he was an active member of the Newfoundland Historical Society and Newfoundland & Labrador Historic Trust, of which he was awarded lifetime membership in 1973, in recognition of his services.

Though based in southeast Placentia for most of his later life, Mac was devoted to documenting and preserving the heritage of his hometown and region. He was a founding member and vice-president of the Conception Bay Museum Association; assisted with establishing the Bristol’s Hope Historical Society; and helped access funding to restore the historic St. Paul’s Anglican Church. Notably, Mac and his wife Marie took on the mantle of their son Jerome and daughter-in-law Pamela after their passing. Mac is often noted as the driving force behind the museum’s early success, despite tragic personal setbacks.

In 1974 he won an award from the American Association for State and Local History, for his “resourcefulness and devoted contribution to the preservation of Newfoundland history.” Presenting the award, Historic Trust president Shane O’Dea said, “There is virtually no one in Newfoundland who has been so devoted to the development of a sense of Newfoundland history and culture.” In 1976 Heritage Canada presented Mac with a prestigious award for his lifetime achievements and diligent work with the Conception Bay Museum Association.

Mac Lee passed away at St. John’s General Hospital on Tuesday, December 21, 1976.

“He was not an acquisitive man. He was truly the unbounded ‘free spirit’ whose affection and loyalty for this rock were as deep as any oak’s. He wanted fiercely that this rock and its inhabitants be better. And in many ways, because of him, we are and will be.

“The history that Mac Lee read, researched and preserved lives on. But what shines out through it all is the man himself. And that is the greatest heritage he gave us.” – Monsignor J.M. O’Brien, 1976

William (“Bill”) Parsons

Born in Harbour Grace in 1907, Bill Parsons moved to St. John’s to work in a bank during the 1920s. In 1929 he returned in time for some of the first transatlantic flights, working as a stringer for the Associated Press (AP). Bill would send AP the flight crew’s time of arrival and departure, the type of plane, weather conditions, and any other pertinent information. His father, photographer Reuben T. Parsons, documented every arrival using a large-view camera with glass plates. However, the plates were too fragile for transportation to AP’s Boston office; so Bill took his own pictures on smaller Kodak film. The films were then rushed to Whitbourne, put aboard an express train ,and five days later would be in Boston for the papers. Many of the original photos taken by Bill and Reuben—including Reuben’s old pictures of Harbour Grace street scenes—still grace the Museum today.

For eight years he worked at the Newfoundland Trawling Co., located at the old Terra Nova Shoes site, and rose to the position of manager. In 1947 he left Harbour Grace again to work as a civilian at the American Air Force base in Goose Bay, Labrador, and returned to his hometown permanently in 1958.

After retiring, Bill taught basic navigation, or coastal pilotage, at St. Francis High School and was an early member of the Conception Bay Museum Association. In 1974 he joined Mac Lee as joint vice-president, eventually becoming the Association’s director.

Bill’s leadership and firsthand knowledge of important Harbour Grace events helped guide the Museum through its early years. He played an important role in gathering information and designing the Museum’s most popular room, the second floor ‘Aviation Room,’ with its collection of photographs—many of them Bill’s own—artifacts and primary documents, such as the Harbour Grace Aviation Trust Co.’s logbook. Robinson-Blackmore published his research and memories of the heyday of transatlantic aviation, The Challenge of the Atlantic: A Photo-Illustrated History of Early Aviation in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, co-authored with Bill Bowman, in 1983.

Gordon Simmons

“I came to Harbour Grace as a young man to teach at St. Francis in 1965. Over the next thirteen years the town and Conception Bay North became an anchor in my life. I developed a great interest in the history of the town and, where I could, I tried to incorporate that history in subjects I was assigned to teach. And then I met Mac Lee, then living in the Lee house on Harvey Street. It would take considerable time to describe this extraordinary man, particularly to those who had never met him. It was through Mac that I met Gordon Simmons.

If one wanted to describe the essence of Gordon Simmons, one need only read John Henry Newman’s essay on ‘The Definition of a Gentleman,’ which wonderfully describes Gordon. He was quiet in demeanor but always with a smile, kind word and gentle wit. He was a devoted reader, a collector of historical information and a promoter of Harbour Grace’s rich heritage. He was a dear friend of Mac’s yet in many ways the antithesis of the outgoing and restless Mr. Lee. They were a perfect duo to undertake, along with many others, the establishment of the Conception Bay Museum. It was Gordon who asked me to be a member of the committee, as young and as uninformed as I was. Just being asked by Gordon Simmons was privilege enough for me.

Though not the official secretary, rather the Chairperson, Gordon brought a studied commitment to the undertaking. He kept meticulous notes and preserved relevant historical material. (I don’t know what was the disposition of his personal papers; as well, I’m not sure what may still reside at the Museum.) He also encouraged me to consider initiating a Junior Historical group at the school to meet with older citizens of the area and record through audio-tape and written word their recollections on important elements of community history. (Sadly, those reports, however meagre and tentative, and once held in the school library, were lost in the fire of April 1973.)”

– Gerard “Ged” Blackmore, former Association member

—

The author would like to dedicate this piece to Dianne Lee, for kind words and encouragement.