This past week, we’ve been busying celebrating the 85th anniversary of Amelia Earhart’s solo transatlantic flight from Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, to Culmore, Londonderry, Northern Ireland. On Saturday, May 20, around five hours and twenty minutes before Earhart’s takeoff, poet Heidi Greco launched her new poetry collection, Flightpaths: The Lost Journals of Amelia Earhart (Caitlin Press, 2017), from which she read to a small gathering of poets, patrons, aviators and historians at the Conception Bay Museum, Harbour Grace. In Flightpaths, Greco reimagines what may have happened to Earhart during her attempt to round the world along the equatorial line, using journal entries, fragmented documents and, well, poetry. Great poetry. However, the true story of Earhart’s 1932 transatlantic crossing from Harbour Grace may be “stranger than fiction.”

Amelia Earhart in Harbour Grace

Bernt Balchen (left), Amelia Earhart (centre) and Lewis L’Esperance (right), Shell Oil representative, on the steps of the old Post Office, Harbour Grace, on May 20, 1932.

Ever since her transatlantic crossing as a passenger in 1928—the first for a woman at the time—from Trepassey, Newfoundland, to Burry Point, Wales, Earhart wanted to conquer the Atlantic Ocean as a pilot, without any help at the controls. On May 19, 1932, she, Ed Gorski, her mechanic, and Bernt Balchen, the prestigious Norwegian aviator, left Teterboro, New Jersey, at 3:15 p.m. and headed to Saint John, New Brunswick. Balchen did most of the flying and even registered Earhart’s Lockheed Vega in his own name, to avoid press attention.

Their eventual destination? Harbour Grace, from which many famed and ill-fated flights had taken off to “challenge the Atlantic.” At 2:00 p.m. local time, Earhart’s single-engine monoplane landed at the airstrip. From there, Earhart went to the Cochrane Hotel for a short rest; Balchen and Gorski stayed at the airfield to prepare the Lockheed Vega for takeoff. At the hotel, Earhart met the proprietress of the iconic establishment, Rose Archibald, whose gifts of tomato juice and a thermos of soup have become legendary in the town’s aviation history and lore.

Local Arthur Rogers then took Earhart and her company back to the airstrip, where she would leave at 7:20 p.m. A video of Earhart leaving Harbour Grace can be found here and on our YouTube page:

The Flight

Four hours out from Harbour Grace, the plane’s exhaust manifold broke, and for the next ten hours flames shooting from the vent threatened the success of the flight. Soon the altimeter malfunctioned, which resulted in Earhart flying blind for five hours. And if that wasn’t enough, she dealt with thick clouds and ice developing on the wings of her aircraft.

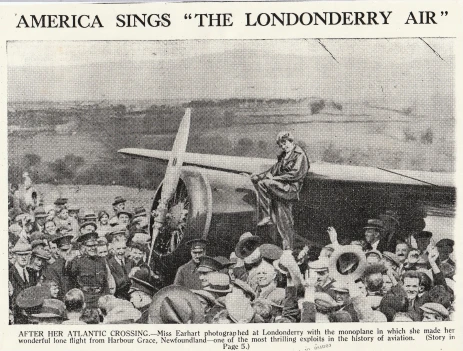

Unable to make it to Paris as Lindbergh had in 1927, Earhart landed in a cow pasture belonging to the Gallagher family, just outside the small hamlet of Culmore, north of Londonderry, Northern Ireland. The record-breaking flight took fourteen hours and fifty-six minutes after her departure from Harbour Grace.

Earhart leaving Londonderry, Northern Ireland, on May 22, 1932.

The Gallaghers offered Earhart a room for the night, which the aviatress accepted, so long as they “didn’t mind her clothes.” Famished, she told Mrs Gallagher that “tomato juice” had been her only meal since leaving America. Recently, BBC Radio Ulster’s Time of Our Lives program recovered Mrs Gallagher’s account of the event. You can listen to the audio here:

The next day, on May 22, Earhart waved the townspeople of Londonderry goodbye and headed for Hanworth Airfield, London, England, where a throng of reporters and fans were ready to greet her.

Earhart’s arrival at Hanworth Airfield, London, England, where reporters were ready to greet her on May 22, 1932.

The flight established Earhart as an international hero, making her the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. For her bravery, Earhart won many honours, including the Gold Medal from the National Geographic Society, presented by United States President Herbert Hoover, the Distinguished Flying Cross from the U.S. Congress, and the Cross of the Knight of the Legion of Honor from the French government.

In Her Own Words

Our (well-worn) copy of Bill Parsons and Bill Bowman’s The Challenge of the Atlantic (Robinson-Blackmore Publishers, 1983).

In The Challenge of the Atlantic: A Photo-Illustrated History of Early Aviation in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland (Robinson-Blackmore Publishers, 1983), Bill Parsons and Bill Bowman’s excellent book on aviation in the town, Earhart’s own account of the flight is related:

“‘My start from Friday from Newfoundland was delayed a little bit to have time to fix up all the customs requirements. They gave me clearance papers, just as if I were Captain of a ship, and I filled a blank space, saying I was going to Paris. I wasn’t sure where I was going, but that did just as well as any other.

‘For the first four hours out I had beautiful weather and I would see the sky and ocean. Everything was lovely.

‘Then, all of a sudden, I ran into rain squalls and heavy wind. Then my exhaust manifold burnt out and bright red flames began shooting out the side.

‘I was not frightened—but it isn’t any fun to have those flames so near you. If there were an oil or gas leak it might cause trouble.

‘Then my altimeter went wrong—the first time in ten years of flying.

‘It was dark and cloudy and raining, and there was nothing for me to do but start climbing. I fixed an easy gradient and kept it up for some time.

‘Then I discovered my tachometer had frozen, so I knew I was high enough, [and] ice formation on my wings made me drop lower.

‘It was only twice after that I caught a glimpse of the ocean. Once I dropped down and saw little white waves under me, but looking down on mountains when man is missing from the picture I had no measure to tell how high the waves were, or how high I was above them—maybe 100 feet, maybe 300. When the morning of Saturday came, I was flying between two layers of clouds. The one below me was composed of little white wooly ones. After a while they all joined together and formed just a great white blanket, like a snowfall stretching in every direction.

‘When the sun broke through the blanket above me it was so blinding that, even with my smoked glasses, I had to come down and fly in the clouds for a while so I could see again.

‘It was here that my eye caught the second glimpse of the ocean. I saw waves running before a northwest wind and, thinking I was pretty far south, I turned due east. The result was that I hit Ireland in about the middle, whereas if I had gone on I probably would have passed the southern tip.

‘There must have been some error in the weather bureau’s calculations, because they thought I would miss the rain altogether. When I got into the squalls I suppose I was to be to the south and kept correcting to the north.

‘I had plenty of fuel and could have kept right on to Paris, maybe further, but my motor was straining; so after sighting land, which I knew must be Ireland, I decided to come down.

‘I could see peat bogs and thatched huts beneath me. I headed north along a railway track and, after a while, flew over Londonderry. Fifteen minutes later I had landed.'”

Parsons and Bowman’s book offers fascinating, detailed accounts, such as the one above, with high-quality photographs as accompaniments. Our friend Lisa Daly, an aviation historian and archaeologist, wrote a favourable review over on her blog, PlaneCrashGirl.ca. If you can track down a copy of The Challenge of the Atlantic, the text is well worth the effort.

Links & Further Information

• Conception Bay Museum: Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | Tumblr | YouTube | Flickr

• Purdue University’s ‘Amelia Earhart Papers’: Airstrip | Lockheed Vega | Earhart

• Earhart media: YouTube | Audioboom

• Lisa Daly: Twitter | PlaneCrashGirl.ca

• The Challenge of the Atlantic: Goodreads | Abebooks

• ‘Hidden Newfoundland’: Airstrip profile

• Town of Harbour Grace: Website | History | Facebook | Twitter